Newt Gingrich turned partisan battles into bloodsport, wrecked Congress, and paved the way for Trump’s rise. Now he’s reveling in his achievements.

Newt Gingrich is an important man, a man of refined tastes, accustomed to a certain lifestyle, and so when he visits the zoo, he does not merely stand with all the other patrons to look at the tortoises—he goes inside the tank.

On this particular afternoon in late March, the former speaker of the House can be found shuffling giddily around a damp, 90‑degree enclosure at the Philadelphia Zoo—a rumpled suit draped over his elephantine frame, plastic booties wrapped around his feet—as he tickles and strokes and paws at the giant shelled reptiles, declaring them “very cool.”

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.It’s a weird scene, and after a few minutes, onlookers begin to gather on the other side of the glass—craning their necks and snapping pictures with their phones and asking each other, Is that who I think it is? The attention would be enough to make a lesser man—say, a sweaty magazine writer who followed his subject into the tortoise tank for reasons that are now escaping him—grow self-conscious. But Gingrich, for whom all of this rather closely approximates a natural habitat, barely seems to notice.

A well-known animal fanatic, Gingrich was the one who suggested we meet at the Philadelphia Zoo. He used to come here as a kid, and has fond memories of family picnics on warm afternoons, gazing up at the giraffes and rhinos and dreaming of one day becoming a zookeeper. But we aren’t here just for the nostalgia.

“There is,” he explained soon after arriving, “a lot we can learn from the natural world.”

Since then, Gingrich has spent much of the day using zoo animals to teach me about politics and human affairs. In the reptile room, I learn that the evolutionary stability of the crocodile (“Ninety million years, and they haven’t changed much”) illustrates the folly of pursuing change for its own sake: “If you’re doing something right, keep doing it.”

Outside the lion pen, Gingrich treats me to a brief discourse on gender theory: “The male lion procreates, protects the pride, and sleeps. The females hunt, and as soon as they find something, the male knocks them over and takes the best portion. It’s the opposite of every American feminist vision of the world—but it’s a fact!”

But the most important lesson comes as we wander through Monkey Junction. Gingrich tells me about one of his favorite books, Chimpanzee Politics, in which the primatologist Frans de Waal documents the complex rivalries and coalitions that govern communities of chimps. De Waal’s thesis is that human politics, in all its brutality and ugliness, is “part of an evolutionary heritage we share with our close relatives”—and Gingrich clearly agrees.

For several minutes, he lectures me about the perils of failing to understand the animal kingdom. Disney, he says, has done us a disservice with whitewashed movies like The Lion King, in which friendly jungle cats get along with their zebra neighbors instead of attacking them and devouring their carcasses. And for all the famous feel-good photos of Jane Goodall interacting with chimps in the wild, he tells me, her later work showed that she was “horrified” to find her beloved creatures killing one another for sport, and feasting on baby chimps.

It is crucial, Gingrich says, that we humans see the animal kingdom from which we evolved for what it really is: “A very competitive, challenging world, at every level.”

As he pauses to catch his breath, I peer out over the sprawling primate reserve. Spider monkeys swing wildly from bar to bar on an elaborate jungle gym, while black-and-white lemurs leap and tumble over one another, and a hulking gorilla grunts in the distance.

At a loss for what to say, I start to mutter something about the viciousness of the animal world—but Gingrich cuts me off. “It’s not viciousness,” he corrects me, his voice suddenly stern. “It’s natural.”

T here’s something about Newt Gingrich that seems to capture the spirit of America circa 2018. With his immense head and white mop of hair; his cold, boyish grin; and his high, raspy voice, he has the air of a late-empire Roman senator—a walking bundle of appetites and excesses and hubris and wit. In conversation, he toggles unnervingly between grandiose pronouncements about “Western civilization” and partisan cheap shots that seem tailored for cable news. It’s a combination of self-righteousness and smallness, of pomposity and pettiness, that personifies the decadence of this era.

In the clamorous story of Donald Trump’s Washington, it would be easy to mistake Gingrich for a minor character. A loyal Trump ally in 2016, Gingrich forwent a high-powered post in the administration and has instead spent the years since the election cashing in on his access—churning out books (three Trump hagiographies, one spy thriller), working the speaking circuit (where he commands as much as $75,000 per talk for his insights on the president), and popping up on Fox News as a paid contributor. He spends much of his time in Rome, where his wife, Callista, serves as Trump’s ambassador to the Vatican and where, he likes to boast, “We have yet to find a bad restaurant.”

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

But few figures in modern history have done more than Gingrich to lay the groundwork for Trump’s rise. During his two decades in Congress, he pioneered a style of partisan combat—replete with name-calling, conspiracy theories, and strategic obstructionism—that poisoned America’s political culture and plunged Washington into permanent dysfunction. Gingrich’s career can perhaps be best understood as a grand exercise in devolution—an effort to strip American politics of the civilizing traits it had developed over time and return it to its most primal essence.

When I ask him how he views his legacy, Gingrich takes me on a tour of a Western world gripped by crisis. In Washington, chaos reigns as institutional authority crumbles. Throughout America, right-wing Trumpites and left-wing resisters are treating midterm races like calamitous fronts in a civil war that must be won at all costs. And in Europe, populist revolts are wreaking havoc in capitals across the Continent.

Twenty-five years after engineering the Republican Revolution, Gingrich can draw a direct line from his work in Congress to the upheaval now taking place around the globe. But as he surveys the wreckage of the modern political landscape, he is not regretful. He’s gleeful.

“The old order is dying,” he tells me. “Almost everywhere you have freedom, you have a very deep discontent that the system isn’t working.”

And that’s a good thing? I ask.

“It’s essential,” he says, “if you want Western civilization to survive.”

O n June 24, 1978, Gingrich stood to address a gathering of College Republicans at a Holiday Inn near the Atlanta airport. It was a natural audience for him. At 35, he was more youthful-looking than the average congressional candidate, with fashionably robust sideburns and a cool-professor charisma that had made him one of the more popular faculty members at West Georgia College.

But Gingrich had not come to deliver an academic lecture to the young activists before him—he had come to foment revolution.

“One of the great problems we have in the Republican Party is that we don’t encourage you to be nasty,” he told the group. “We encourage you to be neat, obedient, and loyal, and faithful, and all those Boy Scout words, which would be great around the campfire but are lousy in politics.”

For their party to succeed, Gingrich went on, the next generation of Republicans would have to learn to “raise hell,” to stop being so “nice,” to realize that politics was, above all, a cutthroat “war for power”—and to start acting like it.

The speech received little attention at the time. Gingrich was, after all, an obscure, untenured professor whose political experience consisted of two failed congressional bids. But when, a few months later, he was finally elected to the House of Representatives on his third try, he went to Washington a man obsessed with becoming the kind of leader he had described that day in Atlanta.

The GOP was then at its lowest point in modern history. Scores of Republican lawmakers had been wiped out in the aftermath of Watergate, and those who’d survived seemed, to Gingrich, sadly resigned to a “permanent minority” mind-set. “It was like death,” he recalls of the mood in the caucus. “They were morally and psychologically shattered.”

But Gingrich had a plan. The way he saw it, Republicans would never be able to take back the House as long as they kept compromising with the Democrats out of some high-minded civic desire to keep congressional business humming along. His strategy was to blow up the bipartisan coalitions that were essential to legislating, and then seize on the resulting dysfunction to wage a populist crusade against the institution of Congress itself. “His idea,” says Norm Ornstein, a political scientist who knew Gingrich at the time, “was to build toward a national election where people were so disgusted by Washington and the way it was operating that they would throw the ins out and bring the outs in.”

Gingrich recruited a cadre of young bomb throwers—a group of 12 congressmen he christened the Conservative Opportunity Society—and together they stalked the halls of Capitol Hill, searching for trouble and TV cameras. Their emergence was not, at first, greeted with enthusiasm by the more moderate Republican leadership. They were too noisy, too brash, too hostile to the old guard’s cherished sense of decorum. They even looked different—sporting blow-dried pompadours while their more camera-shy elders smeared Brylcreem on their comb-overs.

Gingrich and his cohort showed little interest in legislating, a task that had heretofore been seen as the primary responsibility of elected legislators. Bob Livingston, a Louisiana Republican who had been elected to Congress a year before Gingrich, marveled at the way the hard-charging Georgian rose to prominence by ignoring the traditional path taken by new lawmakers. “My idea was to work within the committee structure, take care of my district, and just pay attention to the legislative process,” Livingston told me. “But Newt came in as a revolutionary.”

For revolutionary purposes, the House of Representatives was less a governing body than an arena for conflict and drama. And Gingrich found ways to put on a show. He recognized an opportunity in the newly installed C- span cameras, and began delivering tirades against Democrats to an empty chamber, knowing that his remarks would be beamed to viewers across the country.

As his profile grew, Gingrich took aim at the moderates in his own party—calling Bob Dole the “tax collector for the welfare state”—and baited Democratic leaders with all manner of epithet and insult: pro-communist, un-American, tyrannical. In 1984, one of his floor speeches prompted a red-faced eruption from Speaker Tip O’Neill, who said of Gingrich’s attacks, “It’s the lowest thing that I’ve ever seen in my 32 years in Congress!” The episode landed them both on the nightly news, and Gingrich, knowing the score, declared victory. “I am now a famous person,” he gloated to The Washington Post.

It’s hard to overstate just how radical these actions were at the time. Although Congress had been a volatile place during periods of American history—with fistfights and canings and representatives bellowing violent threats at one another—by the middle of the 20th century, lawmakers had largely coalesced around a stabilizing set of norms and traditions. Entrenched committee chairs may have dabbled in petty corruption, and Democratic leaders may have pushed around the Republican minority when they were in a pinch, but as a rule, comity reigned. “Most members still believed in the idea that the Framers had in mind,” says Thomas Mann, a scholar who studies Congress. “They believed in genuine deliberation and compromise … and they had institutional loyalty.”

This ethos was perhaps best embodied by Republican Minority Leader Bob Michel, an amiable World War II veteran known around Washington for his aversion to swearing—doggone it and by Jiminy were fixtures of his vocabulary—as well as his penchant for carpooling and golfing with Democratic colleagues. Michel was no liberal, but he believed that the best way to serve conservatism, and his country, was by working honestly with Democratic leaders—pulling legislation inch by inch to the right when he could, and protecting the good faith that made aisle-crossing possible.

Gingrich was unimpressed by Michel’s conciliatory approach. “He represented a culture which had been defeated consistently,” he recalls. More important, Gingrich intuited that the old dynamics that had produced public servants like Michel were crumbling. Tectonic shifts in American politics—particularly around issues of race and civil rights—had triggered an ideological sorting between the two parties. Liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats (two groups that had been well represented in Congress) were beginning to vanish, and with them, the cross-party partnerships that had fostered cooperation.

This polarization didn’t originate with Gingrich, but he took advantage of it, as he set out to circumvent the old power structures and build his own. Rather than letting the party bosses in Washington decide which candidates deserved institutional support, he took control of a group called gopac and used it to recruit and train an army of mini-Newts to run for office.

Gingrich hustled to keep his cause—and himself—in the press. “If you’re not in The Washington Post every day, you might as well not exist,” he told one reporter. His secret to capturing headlines was simple, he explained to supporters: “The No. 1 fact about the news media is they love fights … When you give them confrontations, you get attention; when you get attention, you can educate.”

Effective as these tactics were in the short term, they had a corrosive effect on the way Congress operated. “Gradually, it went from legislating, to the weaponization of legislating, to the permanent campaign, to the permanent war,” Mann says. “It’s like he took a wrecking ball to the most powerful and influential legislature in the world.”

But Gingrich looks back with pride on the transformations he set in motion. “Noise became a proxy for status,” he tells me. And no one was noisier than Newt.

We are in the petting zoo, examining the goats, when Gingrich decides to tell me about the moment he first glimpsed his destiny as one of history’s great men.

It was 1958, and he was 15 years old. His family was visiting Verdun, a small city in northeastern France where 300,000 people had been killed during World War I. The battlefield was still scarred by cannon fire, and young Newt spent the day wandering around, taking in the details. He found a rusted helmet on the ground, saw the ossuary where the bones of dead soldiers were piled high. “I realized countries can die,” he says—and he decided it would be up to him to make sure that America didn’t.

This is an important scene in the Newt Gingrich creation myth, and he has turned to it repeatedly over the years to satisfy journalists and biographers searching for a “Rosebud” moment. But the rest of Gingrich’s childhood may be just as instructive. His mother struggled with manic depression, and spent much of her adult life in a fog of medication. His stepfather was a brooding, violent man who showed little affection for “Newtie,” the pudgy, flat-footed, bookish boy his wife had foisted upon him. Gingrich moved around a lot and had few friends his age; he spent more time alone in his room reading books about dinosaurs than he did playing with the neighborhood kids.

But this is not the stuff Gingrich likes to talk about. When asked, he describes his childhood as ordinary, even “idyllic,” allowing only glimpses of the full picture when you press him for details. Those family picnics at the zoo that he has been reminiscing about all day? They weren’t with his parents, it turns out, but his aunts, who were looking for ways to make their lonely nephew happy.

“People like me are what stand between us and Auschwitz,” Gingrich once told a reporter.

It was in Verdun that Gingrich found an identity, a sense of purpose. “I decided then that I basically had three jobs,” he tells me. “Figure out what we had to do to survive”—the we here being proponents of Western civilization, the threats being vague and unspecified—“figure out how to explain it so that the American people would give us permission, and figure out how to implement it once they gave us permission. That’s what I’ve done since August of ’58.”

The next year, Gingrich turned in a 180-page term paper about the balance of global power, and announced to his teacher that his family was moving to Georgia, where he planned to start a Republican Party in the then–heavily Democratic state and get himself elected to Congress.

Gingrich immersed himself in war histories and dystopian fiction and books about techno-futurism—and as the years went on, he became fixated on the idea that he was a world-historic hero. He has described himself as a “transformational figure” and “the most serious, systematic revolutionary of modern times.” To one reporter, he declared, “I want to shift the entire planet. And I’m doing it.” To another, he said, “People like me are what stand between us and Auschwitz.”

As Gingrich tells me about his epiphany in Verdun, a man in a baseball cap approaches us in full fanboy mode. “Newt Gingrich!” he exclaims. “Good to see you, man. I love you on Fox.”

“Thank you,” Gingrich replies. “Please keep watching.”

This has been happening all day—fans coming up to request selfies, or to shake his hand, or to thank him for his work in “draining the swamp.” It’s a reminder that to a certain swath of America, Gingrich is not some washed-up partisan hack; he’s a towering statesman, a visionary hero, the man he set out to be.

After the superfan leaves, I make a passing observation about how many admirers Gingrich has at the zoo.

“I think you’d be surprised,” he tells me, his voice dripping with condescension. “You get outside of Washington and New York and there are an amazing number of people like this who show up.”

B y 1988, Gingrich’s plan to conquer Congress via sabotage was well under way. As his national profile had risen, so too had his influence within the Republican caucus—his original quorum of 12 disciples having expanded to dozens of sharp-elbowed House conservatives who looked to him for guidance.

Gingrich encouraged them to go after their enemies with catchy, alliterative nicknames—“Daffy Dukakis,” “the loony left”—and schooled them in the art of partisan blood sport. Through gopac , he sent out cassette tapes and memos to Republican candidates across the country who wanted to “speak like Newt,” providing them with carefully honed attack lines and creating, quite literally, a new vocabulary for a generation of conservatives. One memo, titled “Language: A Key Mechanism of Control,” included a list of recommended words to use in describing Democrats: sick, pathetic, lie, anti-flag, traitors, radical, corrupt.

“People started asking, ‘Who’s the meanest, nastiest son of a bitch we can get to fight back?’ And, of course, that was Newt Gingrich.”

The goal was to reframe the boring policy debates in Washington as a national battle between good and evil, white hats versus black—a fight for the very soul of America. Through this prism, any news story could be turned into a wedge. Woody Allen had an affair with his partner’s adoptive daughter? “It fits the Democratic Party platform perfectly,” Gingrich declared. A deranged South Carolina woman murdered her two children? A symptom of a “sick” society, Gingrich intoned—and “the only way you can get change is to vote Republican.”

Gingrich was not above mining the darkest reaches of the right-wing fever swamps for material. When Vince Foster, a staffer in the Clinton White House, committed suicide, Gingrich publicly flirted with fringe conspiracy theories that suggested he had been assassinated. “He took these things that were confined to the margins of the conservative movement and mainstreamed them,” says David Brock, who worked as a conservative journalist at the time, covering the various Clinton scandals, before later becoming a Democratic operative. “What I think he saw was the potential for using them to throw sand in the gears of Clinton’s ability to govern.”

Despite his growing grassroots following, Gingrich remained unpopular among a certain contingent of congressional Republicans, who were scandalized by his tactics. But that started to change when Democrats elected Texas Congressman Jim Wright as speaker. Whereas Tip O’Neill had been known for working across party lines, Wright came off as gruff and power-hungry—and his efforts to sideline the Republican minority enraged even many of the GOP’s mild-mannered moderates. “People started asking, ‘Who’s the meanest, nastiest son of a bitch we can get to fight back?’ ” recalls Mickey Edwards, a Republican who was then representing Oklahoma in the House. “And, of course, that was Newt Gingrich.”

Gingrich unleashed a smear campaign aimed at taking Wright down. He reportedly circulated unsupported rumors about a scandal involving a teenage congressional page, and tried to tie Wright to shady foreign-lobbying practices. Finally, one allegation gained traction—that Wright had used $60,000 in book royalties to evade limits on outside income. Watergate, this was not. But it was enough to force Wright’s resignation, and hand Gingrich the scalp he so craved.

The episode cemented Gingrich’s status as the de facto leader of the GOP in Washington. Heading into the 1994 midterms, he rallied Republicans around the idea of turning Election Day into a national referendum. On September 27, more than 300 candidates gathered outside the Capitol to sign the “Contract With America,” a document of Gingrich’s creation that outlined 10 bills Republicans promised to pass if they took control of the House.

“Today, on these steps, we offer this contract as a first step towards renewing American civilization,” Gingrich proclaimed.

While candidates fanned out across the country to campaign on the contract, Gingrich and his fellow Republican leaders in Congress held fast to their strategy of gridlock. As Election Day approached, they maneuvered to block every piece of legislation they could—even those that might ordinarily have received bipartisan support, like a lobbying-reform bill—on the theory that voters would blame Democrats for the paralysis.

Pundits, aghast at the brazenness of the strategy, predicted backlash from voters—but few seemed to notice. Even some Republicans were surprised by what they were getting away with. Bill Kristol, then a GOP strategist, marveled at the success of his party’s “principled obstructionism.” An up-and-coming senator named Mitch McConnell was quoted crowing that opposing the Democrats’ agenda “gives gridlock a good name.” When the 103rd Congress adjourned in October, The Washington Post declared it “perhaps the worst Congress” in 50 years.

Yet Gingrich’s plan worked. By the time voters went to the polls, exit surveys revealed widespread frustration with Congress and a deep appetite for change. Republicans achieved one of the most sweeping electoral victories in modern American history. They picked up 54 seats in the House and seized state legislatures and governorships across the country; for the first time in 40 years, the GOP took control of both houses of Congress.

On election night, Republicans packed into a ballroom in the Atlanta suburbs, waving placards that read liberals, your time is up! and sporting rush limbaugh for president T‑shirts. The band played “Happy Days Are Here Again” and Gingrich—the next speaker of the House, the new philosopher-king of the Republican Party—took the stage to raucous cheers.

With victory in hand, Gingrich did his best to play the statesman, saying he would “reach out to every Democrat who wants to work with us” and promising to be “speaker of the House, not speaker of the Republican Party.”

But the true spirit of the Republican Revolution was best captured by the event’s emcee, a local talk-radio host in Atlanta who had hitched his star to the Newt wagon early on. Grinning out at the audience, he announced that a package had just arrived at the White House with some Tylenol in it.

President Clinton, joked Sean Hannity, was about to “feel the pain.”

T he freshman Republicans who entered Congress in January 1995 were lawmakers created in the image of Newt: young, confrontational, and determined to inflict radical change on Washington.

Gingrich encouraged this revolutionary zeal, quoting Thomas Paine—“We have it in our power to begin the world over again”—and working to instill a conviction among his followers that they were political gate-crashers, come to leave their dent on American history. What Gingrich didn’t tell them—or perhaps refused to believe himself—was that in Congress, history is seldom made without consensus-building and horse-trading. From the creation of interstate highways to the passage of civil-rights legislation, the most significant, lasting acts of Congress have been achieved by lawmakers who deftly maneuver through the legislative process and work with members of both parties.

On January 4, Speaker Gingrich gaveled Congress into session, and promptly got to work transforming America. Over the next 100 days, he and his fellow Republicans worked feverishly to pass bills with names that sounded like they’d come from Republican Mad Libs—the American Dream Restoration Act, the Taking Back Our Streets Act, the Fiscal Responsibility Act. But when the dust settled, America didn’t look all that different. Almost all of the House’s big-ticket bills got snuffed out in the Senate, or died by way of presidential veto.

Instead, the most enduring aspects of Gingrich’s speakership would be his tactical innovations. Determined to keep Republicans in power, Gingrich reoriented the congressional schedule around filling campaign war chests, shortening the official work week to three days so that members had time to dial for dollars. From 1994 to 1998, Republicans raised an unprecedented $1 billion, and ushered in a new era of money in politics.

Gingrich’s famous budget battles with Bill Clinton in 1995 gave way to another great partisan invention: the weaponized government shutdown. There had been federal funding lapses before, but they tended to be minor affairs that lasted only a day or two. Gingrich’s shutdown, by contrast, furloughed hundreds of thousands of government workers for several weeks at Christmastime, so Republicans could use their paychecks as a bartering chip in negotiations with the White House. The gambit was a bust—voters blamed the GOP for the crisis, and Gingrich was castigated in the press—but it ensured that the shutdown threat would loom over every congressional standoff from that point on.

There were real accomplishments during Gingrich’s speakership, too—a tax cut, a bipartisan health-care deal, even a balanced federal budget—and for a time, truly historic triumphs seemed within reach. Over the course of several secret meetings at the White House in the fall of 1997, Gingrich told me, he and Clinton sketched out plans for a center-right coalition that would undertake big, challenging projects such as a wholesale reform of Social Security.

But by then, the poisonous politics Gingrich had injected into Washington’s bloodstream had escaped his control. So when the stories started coming out in early 1998—the ones about the president and the intern, the cigar and the blue dress—and the party faithful were clamoring for Clinton’s head on a pike, and Gingrich’s acolytes in the House were stomping their feet and crying for blood … well, he knew what he had to do.

This is “the most systematic, deliberate obstruction-of-justice cover-up and effort to avoid the truth we have ever seen in American history!” Gingrich declared of the Monica Lewinsky scandal, pledging that he would keep banging the drum until Clinton was impeached. “I will never again, as long as I am speaker, make a speech without commenting on this topic.”

Never mind that Republicans had no real chance of getting the impeachment through the Senate. Removing the president wasn’t the point; this was an opportunity to humiliate the Democrats. Politics was a “war for power,” just as Gingrich had prophesied all those years ago—and he wasn’t about to give up the fight.

The rest is immortalized in the history books that line Gingrich’s library. The GOP’s impeachment crusade backfired with voters, Republicans lost seats in the House—and Gingrich was driven out of his job by the same bloodthirsty brigade he’d helped elect. “I’m willing to lead,” he sniffed on his way out the door, “but I’m not willing to preside over people who are cannibals.”

T he great irony of Gingrich’s rise and reign is that, in the end, he did fundamentally transform America—just not in the ways he’d hoped. He thought he was enshrining a new era of conservative government. In fact, he was enshrining an attitude—angry, combative, tribal—that would infect politics for decades to come.

In the years since he left the House, Gingrich has only doubled down. When GOP leaders huddled at a Capitol Hill steak house on the night of President Barack Obama’s inauguration, Gingrich was there to advocate a strategy of complete obstruction. And when Senator Ted Cruz led a mob of Tea Party torchbearers in shutting down the government over Obamacare, Gingrich was there to argue that shutdowns are “a normal part of the constitutional process.”

Mickey Edwards, the Oklahoma Republican, who served in the House for 16 years, told me he believes Gingrich is responsible for turning Congress into a place where partisan allegiance is prized above all else. He noted that during Watergate, President Richard Nixon was forced to resign only because leaders of his own party broke ranks to hold him accountable—a dynamic Edwards views as impossible in the post-Gingrich era. “He created a situation where you now stand with your party at all costs and at all times, no matter what,” Edwards said. “Our whole system in America is based on the Madisonian idea of power checking power. Newt has been a big part of eroding that.”

But when I ask Gingrich what he thinks of the notion that he played a part in toxifying Washington, he bristles. “I took everything the Democrats had done brilliantly to dominate and taught Republicans how to do it,” he tells me. “Which made me a bad person because when Republicans dominate, it must be bad.” He adopts a singsong whine to imitate his critics in the political establishment: “ ‘Oh, the mean, nasty Republicans actually got to win, and we hate it, because we’re a Democratic city, our real estate’s based on big government, and the value of my house will go down if they balance the budget.’ That’s the heart of this.”

These days, Gingrich seems to be revising his legacy in real time—shifting the story away from the ideological sea change that his populist disruption was supposed to enable, and toward the act of populist disruption itself. He places his own rise to power and Trump’s in the same grand American narrative. There have been four great political “waves” in the past half century, he tells me: “Goldwater, Reagan, Gingrich, then Trump.” But when I press him to explain what connects those four “waves” philosophically, the best he can do is say they were all “anti-liberal.”

Political scientists who study our era of extreme polarization will tell you that the driving force behind American politics today is not actually partisanship, but negative partisanship—that is, hatred of the other team more than loyalty to one’s own. Gingrich’s speakership was both a symptom and an accelerant of that phenomenon.

On December 19, 1998, Gingrich cast his final vote as a congressman—a vote to impeach Bill Clinton for lying under oath about an affair. By the time it was revealed that the ex-speaker had been secretly carrying on an illicit relationship with a young congressional aide named Callista throughout his impeachment crusade, almost no one was surprised.* This was, after all, the same man who had famously been accused by his first wife (whom he’d met as a teenager, when she was his geometry teacher) of trying to discuss divorce terms when she was in the hospital recovering from tumor-removal surgery, the same man who had for a time reportedly restricted his extramarital dalliances to oral sex so that he could claim he’d never slept with another woman. (Gingrich declined to comment on these allegations.)

Detractors could call it hypocrisy if they wanted; Gingrich might not even argue. (“It doesn’t matter what I do,” he once rationalized, according to one of his ex-wives. “People need to hear what I have to say.”) But if he had taught America one lesson, it was that any sin could be absolved, any trespass forgiven, as long as you picked the right targets and swung at them hard enough.

When Gingrich’s personal life became an issue during his short-lived presidential campaign in 2012, he knew just who to swing at. Asked during a primary debate about an allegation that he’d requested an open marriage with his second wife, Gingrich took a deep breath, gathered all the righteous indignation he could muster, and let loose one of the most remarkable—and effective—non sequiturs in the history of campaign rhetoric: “I think the destructive, vicious, negative nature of much of the news media makes it harder to govern this country, harder to attract decent people to run for public office—and I am appalled that you would begin a presidential debate on a topic like that.”

The CNN moderator grew flustered, the audience erupted in a standing ovation, and a few days later, the voters of South Carolina delivered Gingrich a decisive victory in the Republican primary.

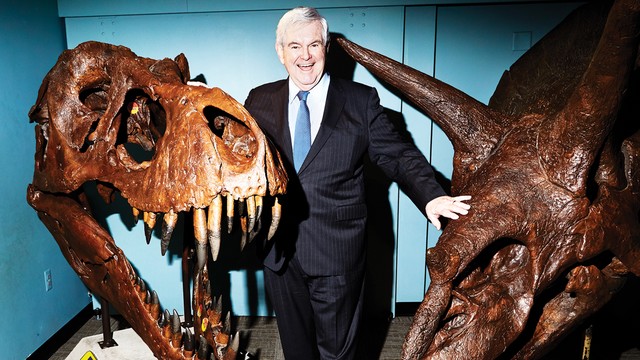

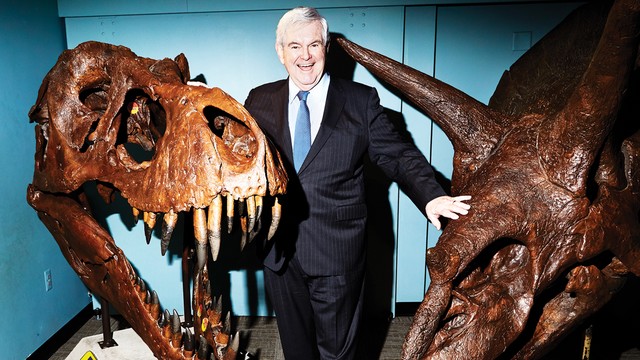

A fter a few hours at the zoo, Gingrich is ready for the next leg of our field trip, so we squeeze into the back of a black SUV and start driving across town toward the Academy of Natural Sciences, where there are some “really neat” dinosaur fossils he would like to show me.

One of the hard things about talking with Gingrich is that he weaves partisan attack lines into casual conversation so matter-of-factly—and so frequently—that after a while they begin to take on a white-noise quality. He will say something like “I mean, the party of socialism and anti-Semitism is probably not very desirable as a governing party,” and you won’t bother challenging him, or fact-checking him, or arching an eyebrow—in fact, you might not even notice. His smarter-than-thou persona seems so impenetrable, his mind so unchangeable, that after a while you just give up on anything approaching a regular human conversation.

But the zoo appears to have put Gingrich in high spirits, and for the first time all day, he seems relaxed, loose, even a little gossipy. Slurping from a McDonald’s cup as we ride through the streets of Philadelphia, he shares stray observations from the 2016 campaign trail—Trump really is a fast-food obsessive, Gingrich confides, but “I’m told they currently have him on a diet”—and tosses in a bit of Clinton concern-trolling for good measure.

“I’ve known Hillary since ’93. I think it would be extraordinarily hard to be married to Bill Clinton and lose twice,” he tells me. “It reinforces the whole sense that he was the real deal and she wasn’t.” Alas, he says, it’s been sad to see his old friend resort to bitter recriminations since her defeat. “The way she is handling it is self-destructive.”

It is difficult to identify any coherent set of ideas animating Gingrich’s support for the president.

When Trump first began thinking seriously about running for president, he turned to Gingrich for advice. The two men had known each other for years—the Gingriches were members of Trump’s golf club in Virginia—and one morning in January 2015 they found themselves in Des Moines, Iowa, for a conservative conference. Over breakfast at the downtown Marriott, Trump peppered Newt and Callista with questions about running for president—most pressingly, how much it would cost him to fund a campaign through the South Carolina primary. Gingrich estimated that it would take about $70 million or $80 million to be competitive.

As Gingrich tells it, Trump considered this and then replied, “Seventy to 80 million—that would be a yacht. This would be a lot more fun than a yacht!”

And so began the campaign that Gingrich would call “a watershed moment for America’s future.” Early on, Gingrich set himself apart from other prominent conservatives by talking up Trump’s candidacy on TV and defending him against attacks from the GOP establishment. “Newt watched the Trump phenomenon take hold and metastasize, and he saw the parallels” to his own rise, says Kellyanne Conway, a senior adviser to the president who worked with Gingrich in the 1990s. “He recognized the echoes of ‘You can’t do this, this is a joke, you’re unelectable, don’t even try, you should be bowing to the people who have credentials.’ Newt had heard that all before.” Trump’s response—to cast all his skeptics as part of the same corrupt class of insiders and crooks—borrowed from the strategy Gingrich had modeled, Conway told me: “Long before there was ‘Drain the swamp,’ there was Newt’s ‘Throw the bums out.’ ”

Once Trump clinched the nomination, he rewarded Gingrich by putting him on the vice-presidential short list. For a while it looked like it might really happen. Gingrich had the support of influential inner-circlers like Sean Hannity, who flew him out on a private jet to meet with Trump on the campaign trail. But alas, a Trump-Gingrich ticket was not to be. There were, it turned out, certain optical issues that would have proved difficult to spin. As Ed Rollins, who ran a pro-Trump super pac , put it at the time, “It’d be a ticket with six former wives, kind of like a Henry VIII thing.”

After Trump was elected, Gingrich’s name was floated for several high-profile administration posts. Eager to affirm his centrality in this hinge-of-history moment, he started publicly implying that he had turned down the job of secretary of state in favor of a sweeping, self-designed role with ambiguous responsibilities—“general planner,” he called it, or “senior planner,” or maybe “chief planner.”

In fact, according to a transition official, Gingrich had little interest in giving up his lucrative private-sector side hustles, and was never really in the running for a Cabinet position. Instead, he had two requests: that Trump’s team leak that he was being considered for high office, and that Callista, a lifelong Catholic, be named ambassador to the Holy See. (Gingrich disputes this account.)

The Vatican gig was widely coveted, and there was some concern that Callista’s public history of adultery would prompt the pope to reject her appointment. But the Gingriches were friendly with a number of American cardinals, and Callista’s nomination sailed through. In Washington, the appointment was seen as a testament to the self-parodic nature of the Trump era—but in Rome, the arrangement has worked surprisingly well. Robert Mickens, a longtime Vatican journalist, told me that Callista is generally viewed as the ceremonial face of the embassy, while Newt—who told me he talks to the White House 10 to 15 times a week—acts as the “shadow ambassador.”

“Donald Trump is the grizzly bear in The Revenant,” Gingrich once gushed. “If you get his attention, he will get awake . He will walk over, bite your face off, and sit on you.”

Meanwhile, back in the States, Gingrich got to work marketing himself as the premier public intellectual of the Trump era. Ever since he was a young congressman, he had labored to cultivate a cerebral image, often schlepping piles of books into meetings on Capitol Hill. As an exercise in self-branding, at least, the effort seems to have worked: When I sent an email asking Paul Ryan what he thought of Gingrich, he responded with a pro forma statement describing the former speaker as an “ideas guy” twice in the space of six sentences.

Yet wading through Gingrich’s various books, articles, and think-tank speeches about Trump, it is difficult to identify any coherent set of “ideas” animating his support for the president. He is not a natural booster for the economic nationalism espoused by people like Steve Bannon, nor does he seem particularly smitten with the isolationism Trump championed on the stump.

Instead, Gingrich seems drawn to Trump the larger-than-life leader—virile and masculine, dynamic and strong, brimming with “total energy” as he mows down every enemy in his path. “Donald Trump is the grizzly bear in The Revenant,” Gingrich gushed during a December 2016 speech on “The Principles of Trumpism” at the Heritage Foundation. “If you get his attention, he will get awake … He will walk over, bite your face off, and sit on you.”

In Trump, Gingrich has found the apotheosis of the primate politics he has been practicing his entire life—nasty, vicious, and unconcerned with those pesky “Boy Scout words” as he fights in the Darwinian struggle that is American life today. “Trump’s America and the post-American society that the anti-Trump coalition represents are incapable of coexisting,” Gingrich writes in his most recent book. “One will simply defeat the other. There is no room for compromise. Trump has understood this perfectly since day one.”

For much of 2018, Gingrich has been channeling his energies toward shaping the GOP’s midterm strategy—writing messaging memos and fielding phone calls from candidates across the country. (During one early-morning meeting a couple of months after our zoo trip, our conversation is repeatedly interrupted by Gingrich’s cellphone blaring the ’70s disco song “Dancing Queen,” his chosen ringtone.) Gingrich tells me he’s advising party leaders to “stick to really big themes” in their midterm messaging, and then offers the following as examples: “Tax cuts lead to economic growth”; “We need work rather than welfare”; “MS-13 is really bad.”

He predicts that if Democrats win back the House, they will try to impeach Trump—but he is bullish about the president’s chances of survival.

“The problem the Democrats are gonna have is really simple,” he tells me. “Everything they’re gonna charge Trump with will be irrelevant to most Americans.” He says that most of the “explosive revelations” that have come out of the Russia investigation are unintelligible to the average person. “You’re driving your kids to soccer, you’re worried about your mom in the nursing home, and you’re thinking about your job, and you’re going, This is Washington crap.”

I ask Gingrich whether he, as someone who follows Washington crap rather closely and does not have kids to drive to soccer, worries at all about the mounting evidence of coordination between Russians and the Trump campaign.

Gingrich guffaws. “The idea that you would worry about what [Michael] Cohen said, or what some porn star may or may not have done before she was arrested by the Cincinnati police”—he is revving up now, and his voice is getting higher—“I mean, this whole thing is a parody! I tell everybody: We live in the age of the Kardashians. This is all Kardashian politics. Noise followed by noise followed by hysteria followed by more noise, creating big enough celebrity status so you can sell the hats with your name on it and become a millionaire.”

This sounds like it’s intended as a criticism of our political culture, but given his loyalty to Trump—arguably the world’s most successful practitioner of “Kardashian politics”—I can’t quite tell. When I point out the apparent dissonance, Gingrich is ready with a counter.

“If you want to see genius, look at the hat,” he tells me. “What does the hat say?”

“Make America great again?” I respond.

Gingrich nods triumphantly, as though he’s just achieved checkmate. “It doesn’t say Donald Trump.”

A few hours after parting ways with Gingrich, I take my seat in a cavernous downtown-Philadelphia theater, where more than 2,000 people are waiting to hear him speak. The crowd of mostly white, mostly well-dressed attendees isn’t particularly partisan—the event is part of a lecture series that includes speakers like Gloria Steinem and Dave Barry—but at this moment of political upheaval, they seem eager to hear from a seasoned Washington insider.

Shortly after 8 o’clock, Gingrich takes the stage. “How many of you find what’s going on kind of confusing?” he asks. “Raise your hand.” Hundreds of hands go up, as laughter ripples across the theater. “Any of you who do not find this confusing,” he says, “are delusional.”

And yet, over the next 75 minutes, Gingrich doesn’t offer much clarity. Instead, he begins with a travelogue of his day at the zoo (“It was a wonderful break from that other zoo!”), and then lurches into a rambling story about the T. rex skull he used to display in his office when he was speaker. He reminisces about Time making him Man of the Year in 1995, and spends several minutes describing the technological advancements in private space travel, a favorite hobbyhorse of his. At one point, he pauses to lavish praise on the restaurant scene in Rome; at another, he simply starts listing impressive titles he has held over the course of his career.

From my seat in the balcony, I’m struck by how thoroughly Gingrich seems to be enjoying himself—not just onstage, but in the luxurious quasi-retirement he has carved out. He is dabbling in geopolitics, dining in fine Italian restaurants. When he feels like traveling, he crisscrosses the Atlantic in business class, opining on the issues of the day from bicontinental TV studios and giving speeches for $600 a minute. There is time for reading, and writing, and midday zoo trips—and even he will admit, “It’s a very fun life.” The world may be burning, but Newt Gingrich is enjoying the spoils.

As he nears the end of his remarks, Gingrich adopts a somber tone. “I will tell you,” he says, “I could never quite have imagined our political structure being as chaotic as it currently is … I could never quite have imagined the kind of political gridlock that we’ve gotten into.”

For a moment, it sounds almost as if Gingrich is on the brink of a confession—an acknowledgment of what he has wrought; an apology, perhaps, for setting us on this course. But it turns out he is just setting up an attack line aimed at congressional Democrats for opposing a Republican spending bill. I should have known.